Pakistani Literature The World Takes Notice

Written By: Insu Anita Lobo

Writing is the one thing that can stay as lively and imaginative as it was when it was first conceived and put into words by the author, the books are always better than the movies, why is that so? Because nothing can beat our own imaginations, the colours, the vividness of the storie s which can be created in one’s head are much more brilliant than any on screen marvel. Writers combine thoughts; knowledge and imagination to create beautiful masterpieces that can be understood, no matter who you are, where you come from or what language you speak. We all have a human connection, and it is this, mystical bond which makes us all different and thus similar in the struggle of the Human Struggle. Thus, the worst of times can eventually become the best of times for a Pakistani writer and poet. So even if Pakistan may face hard times, the world’s eyes are constantly trained not just on it but on the tales emerging from the country. For the writers of Pakistan trying times can be used to inspire great writing that can describe the triumphs out of struggle for it is these times in which inspiration can be found, and shine hope in the darkness. A new wave of Pakistani writers in the English genre is now winning literary acclaim as they seamlessly move between London, Karachi, New York and Lahore. Dealing with a heady mix of social and political themes, the writers are flirting with stories of war, loss, love and, of course, conflict. Pakistan may be in the spotlight of some of the world’s problems but it has allowed writers and artists to explain their views and the world now takes notice. The Pakistani Author Nadeem Aslam’s novel, The Wasted Vigil, explores the complexities and fallout of war and how not just countries but their people suffer. Set in modern Afghanistan, Aslam says he wanted to create a portrait of the conflicts that shape our world and relate the identities of characters a

s which can be created in one’s head are much more brilliant than any on screen marvel. Writers combine thoughts; knowledge and imagination to create beautiful masterpieces that can be understood, no matter who you are, where you come from or what language you speak. We all have a human connection, and it is this, mystical bond which makes us all different and thus similar in the struggle of the Human Struggle. Thus, the worst of times can eventually become the best of times for a Pakistani writer and poet. So even if Pakistan may face hard times, the world’s eyes are constantly trained not just on it but on the tales emerging from the country. For the writers of Pakistan trying times can be used to inspire great writing that can describe the triumphs out of struggle for it is these times in which inspiration can be found, and shine hope in the darkness. A new wave of Pakistani writers in the English genre is now winning literary acclaim as they seamlessly move between London, Karachi, New York and Lahore. Dealing with a heady mix of social and political themes, the writers are flirting with stories of war, loss, love and, of course, conflict. Pakistan may be in the spotlight of some of the world’s problems but it has allowed writers and artists to explain their views and the world now takes notice. The Pakistani Author Nadeem Aslam’s novel, The Wasted Vigil, explores the complexities and fallout of war and how not just countries but their people suffer. Set in modern Afghanistan, Aslam says he wanted to create a portrait of the conflicts that shape our world and relate the identities of characters a nd situations in the book to how the current struggles take place.

nd situations in the book to how the current struggles take place.

We see this when we look at Mohsin Hamid’s first novel, Moth Smoke published in 2000, which was set against the backdrop of the Indian-Pakistani arms race. And his second and highly acclaimed The Reluctant Fundamentalist published in 2007 explored the aftermath of 9/11 and the international unease it unleashed. Hamid chose the monologue to narrate his story and his Pakistani protagonist tells his tale to a nameless American who sits across from him in a Lahore cafe.

In 2008 came the first real English language political parody in Pakistan. The author Mohammad Hanif’s first novel, A Case of Exploding Mangoes, is an open deride of Islamic fundament-alism and the plots and counter-plots taking place during General Zia ul Haq’s rule in the 1980s. But Pakistani writers have many more subjects to deliberate on than just politics. Pakistani writing is very diverse now. Mohammad Hanif mentions in one of his interviews with Gupshup that ‘There’s a lot of ambition in the [Pakistani] writing and no subject is taboo.’

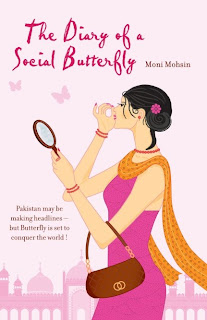

Another auth or Moni Mohsin says that ‘Pakistani fiction is changing as writers are experim-enting with new genres and new subjects,’ Moni believes that since Pakistanis have been exposed to and witnessed a fair amount of political and social upheaval, that it is bound to find a route to expression in Pakistani fiction. But that is not to say that Pakistani writers are restricting themselves to such a view, rather in her own book, The Diary of a Social Butterfly, which is a light-hearted comedy and one that mocks a privileged strata of Pakistani society. The Diary of a Social Butterfly began as a column in Pakistan’s Friday Times and its central character is Butterfly, a silly socialite, the column was then compiled into a book which speaks a kind of Lahori English.

or Moni Mohsin says that ‘Pakistani fiction is changing as writers are experim-enting with new genres and new subjects,’ Moni believes that since Pakistanis have been exposed to and witnessed a fair amount of political and social upheaval, that it is bound to find a route to expression in Pakistani fiction. But that is not to say that Pakistani writers are restricting themselves to such a view, rather in her own book, The Diary of a Social Butterfly, which is a light-hearted comedy and one that mocks a privileged strata of Pakistani society. The Diary of a Social Butterfly began as a column in Pakistan’s Friday Times and its central character is Butterfly, a silly socialite, the column was then compiled into a book which speaks a kind of Lahori English.

We see more of diversity in the topic of discussion amongst new authors which have come into the Literary Scene. It is clear from two eagerly awaited works that have reached bookstores: Kamila Shamsie’s fifth and reportedly finest novel, Burnt Shadows, and a collection of short stories by Daniyal Muee-nuddin. Kamila Shamsie’s story is a saga that does not focus on politics but rather it intertwines the lives of two families over a period of 50 years. Her narrative goes through the devastation of Nagasaki in WW II through the conflict-ridden formation of Pakistan in the late 1940s to post-9/11 Manhattan and war-torn Afghanistan.

Literary Scene. It is clear from two eagerly awaited works that have reached bookstores: Kamila Shamsie’s fifth and reportedly finest novel, Burnt Shadows, and a collection of short stories by Daniyal Muee-nuddin. Kamila Shamsie’s story is a saga that does not focus on politics but rather it intertwines the lives of two families over a period of 50 years. Her narrative goes through the devastation of Nagasaki in WW II through the conflict-ridden formation of Pakistan in the late 1940s to post-9/11 Manhattan and war-torn Afghanistan.

We see Mueenuddin revive the short story genre which discusses the topics of farm managers, servants, landlords and political fixers which are similar to Pakistani culture.

Mohsin H amid is one author to take notice, his book The Reluctant Fundamentalist was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2007, he is notably the first Pakistani writer to make a debut on the list which lead to the spark for other Pakistani writers in the international literary arena, He says to The Telegraph Calcutta: ‘There’s something very powerful and fresh happening in Pakistani letters at the moment.’ He strongly believes that there is exciting development brought by the writing of Mohammed Hanif and Daniyal Mueenuddin in the space of year whe n their books debuted. He says that ‘Neither Pakistan nor India has produced anything like them before.’

amid is one author to take notice, his book The Reluctant Fundamentalist was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2007, he is notably the first Pakistani writer to make a debut on the list which lead to the spark for other Pakistani writers in the international literary arena, He says to The Telegraph Calcutta: ‘There’s something very powerful and fresh happening in Pakistani letters at the moment.’ He strongly believes that there is exciting development brought by the writing of Mohammed Hanif and Daniyal Mueenuddin in the space of year whe n their books debuted. He says that ‘Neither Pakistan nor India has produced anything like them before.’

Nadeem Aslam who is reported earlier says that compared to Indian writing, Pakistani writing is still in its infancy and needs time to grow and to take command. And that while Indian writers have been around for 25 years or so, Pakistani authors are only just beginning derive attention especially in the international arena.

Today if eyes have noticed Pakistani authors, it is because the few authors who have released their books have made very interesting contri-butions to the Literary scene during the last couple of years and are expecting more in future. We see international exposure to our writers with the Karachi Literature Festival which is the first of its kind, organised and hosted by the British Council Pakistan in association with Oxford University Press in March of this year. The Festival was also affluently discussed and celebrated by Dawn and on the international media front, the festival was discussed in detail by UK’s The Inde-pendent, India’s Hindustan Times and Times of India, and New Zealand’s Herald. BBC Radio’s Urdu Service also covered the event, showing that our literary exposure is finally kicking off, and may lead us into major international events before long.

of years and are expecting more in future. We see international exposure to our writers with the Karachi Literature Festival which is the first of its kind, organised and hosted by the British Council Pakistan in association with Oxford University Press in March of this year. The Festival was also affluently discussed and celebrated by Dawn and on the international media front, the festival was discussed in detail by UK’s The Inde-pendent, India’s Hindustan Times and Times of India, and New Zealand’s Herald. BBC Radio’s Urdu Service also covered the event, showing that our literary exposure is finally kicking off, and may lead us into major international events before long.

A host of new names have also joined the Pakistani literary circle. Penguin books is excited about, Harvard-educated Ali Sethi’s debut novel The Wish Maker, which is a family saga and Fatima Bhutto’s book on the history of the Bhutto family.

Uzma Aslam Khan’s third novel, The Geometry of God, has been published in the US, Italy, and France and has been released in Spain. She has also written an essay-style piece called Flagging Multi-culturalism: How American Insularity Morally Justifies Itself, which has been pu blished by Atlas Books USA in their anthology How They See Us later this year.

The Authors feel that many factors have come together to create the right conditions for the emergence of Pakistani literary fiction. Also, today, Western publishers are constantly seeking the next ‘new’ thing and they have suddenly turned their attention to Pakistan. In addition, a growing number of young Pakistanis are receiving degrees in creative writing from well-regarded Western universities and there’s an explosion in home grown newspapers, magazines and periodicals creating a new generation of writers and readers.

In the days when Hanif went in search of a Pakistani publisher for A Case of Exploding Mangoes and couldn’t find one the newer writers have found it much easier than before. He remembers when most thought the book wouldn’t have any readership and one publisher even told Hanif that they could probably sell three copies. But now with the release of his book Hanif says more authors have debuted in the literary exchange with more of them getting attention from T.V. and Websites, it has opened routes to help them publish their books.

when Hanif went in search of a Pakistani publisher for A Case of Exploding Mangoes and couldn’t find one the newer writers have found it much easier than before. He remembers when most thought the book wouldn’t have any readership and one publisher even told Hanif that they could probably sell three copies. But now with the release of his book Hanif says more authors have debuted in the literary exchange with more of them getting attention from T.V. and Websites, it has opened routes to help them publish their books.

We cannot assume that it the country’s current crisis that is exposing Pakistani authors to the international market in the works of Pakistani writers Uzma Aslam Khan says ‘That it’s very dangerous to expect writers from anywhere, including Pakistan, to speak in the same voice as news anchors. I think that this expectation is being put on us, at times very overtly,’ as reported by Pak Tea House.

It could be seen that Pakistan may be in the headlines for all the wrong reasons but authors like Rakshanda Jalil say firmly that Pakistani writers are not playing to the gallery. ‘Though political unrest usually spawns good literature, Pakistani authors are not performing with one eye trained on the pantheon of Western critics and the other on agents who will get them lucrative deals.’ Rather, they are finding their own individual voice. We must remember it is one honest word which is louder than a crowd. The Literary prospects for Pakistani writers is ever growing and full of vast potential, the writers of our past have infused in the culture of today and allowed new and fresh views to establish the ground routes of how life is now. We can only hope that the individual voice is strong enough to brave the test of time and steer hands with the future.

0 Response to "Pakistani Literature The World Takes Notice"

Post a Comment